exploring a London’s borough’s public statuary

A generation ago, public statuary in the UK was given fairly short shrift. The Public Monuments and Sculpture Association (PMSA) was founded in 1991 to rectify this, and one of its most enduring achievements has been the scholarly series, Public Sculpture of Britain, of which this forms volume 22. For various reasons, the PMSA folded in 2020 but the series kept going, under the aegis of the Public Statues and Sculpture Association (PSSA), which rose from the PMSA’s ashes.

Thank heavens it did. The year 2020 saw the Colston summer, when statues—as never before—became targets for protest. In that year the PSSA held an online seminar, “Toppling Statues” (later published as a book), which addressed the issues of outrage and monumentality. How can you balance indignation towards what a statue is felt to embody with an appreciation of its aesthetic and historic merits? Never has there been a clearer need for dispassionate, reliable, scholarly and observant study of monuments as now. The afterword to this book is a thoughtful essay by the founders of the PSSA, which urges a “retain-and-explain” approach.

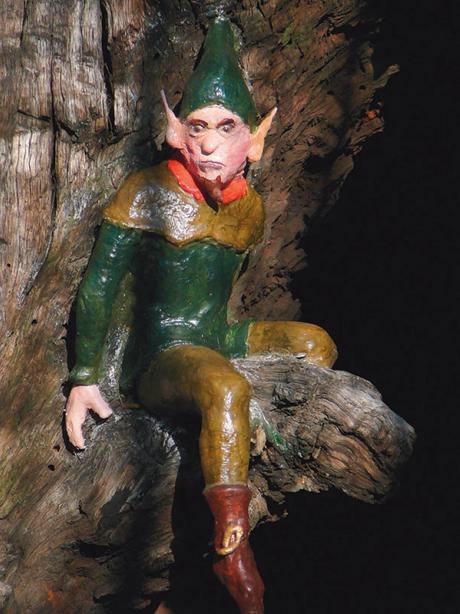

This is Terry Cavanagh’s fourth volume in the series, and it is the largest so far (and beautifully produced). From celebrated statues to hidden pieces, this survey covers the ground surely and with an acute eye. With Chelsea, Hyde Park, Kensington Gardens and Albertopolis within the borders of the book, the sculptural interest level is consistently high. In Kensington Gardens, unveiled in 1907, G.F. Watts’s Physical Energy—which the artist was proud to offer up as a tribute to Cecil Rhodes—is one of the stars. Another is Jacob Epstein’s Rima (1925), close by in Hyde Park, a bold relief tribute to the naturalist and writer W.H. Hudson, which was profoundly controversial in its day. Lesser items like Ivor Innes’s pixie-encrusted Elfin Oak of 1911 get full treatment as well.

Exceptional array

Kensington and Chelsea is a royal borough, and there is an exceptional array of royal monuments. The Albert Memorial leads the pack; not so far away is the intriguing 1908 bronze statue of William III by Heinrich Baucke, given by the Kaiser in 1907. Nearby is Ian Rank-Broadley’s 2021 group, Diana, Princess of Wales, outside Kensington Palace—the most prominent example of the popular modern genre of the realistic bronze figure. Most topical is Leo Mol’s St Volodymyr (1988) in Holland Park Avenue, now a focus for Ukrainian identity, erected on the thousandth anniversary of Ukraine’s adopting Christianity.

Each is of greater interest for what is embodied, rather than as a work of art. There is a touch of the Action Man plastic doll about Hugo Daini’s Simón Bolívar (1974) in Belgrave Square. Carmody Groarke’s 52 steel stelae to the victims of the 7/7 bombings in 2005 in Hyde Park is the leading example of the Modernist memorial to be included here.

Church monuments and cemetery tombs (in Kensal Green and Brompton Cemeteries, which make up a large proportion of the borough’s green space) for once get the coverage they deserve. Chelsea Old Church has a rich crop of memorials, including the unexpected essay in Roman Baroque to Lady Jane Cheyne (died 1669) from the Bernini workshop, which survived the destruction of the church in 1941. And Holy Trinity Sloane Street is full of notable sculpture: a tribute to the Arts and Crafts ideal of the unity of all arts.

Kensal Green gets proper treatment and prompts regret that outdoor memorials became a dwindling forum for displaying the work of leading sculptors. Godfrey Sykes’s terracotta canopy tomb to the painter William Mulready (died 1866) won a silver medal at the 1867 Paris Exposition Universelle for its manufacturers, Messrs. Pulham of Broxbourne, and survives in remarkably crisp condition. Cavanagh’s coverage is consistently scholarly, comprehensive and fascinating.

Architectural sculpture receives equal treatment for once: Harrods department store boasts a pediment of Doulton ware, starring Britannia as the fount of plenty, over a Latin inscription meaning “Everything for everybody, everywhere.” That is not a bad motto for public sculpture.

• Roger Bowdler is a partner at Montagu Evans, advising owners on historic buildings. He was the director of listing at Historic England and writes on funerary art

• Terry Cavanagh, Public Sculpture of Kensington and Chelsea with Westminster Southwest, Public Statues and Sculpture Association, 520pp, colour and b/w illustrations, £85 (hb) £35 (pb), published 3 January

Source link